Project 3: Inequality Sensitive Optimal Treatment Assignment

The material below is based on the paper Inequality Sensitive Optimal Treatment Assignment, by Eduardo Zambrano.

Introduction

This is the third in a series of projects which aim to develop an integrated statistical framework for analyzing distributional impacts in interventions, building on modern welfare economic theory.

In this project, I extend the optimal treatment choice apparatus described in Manski 2024 to the case where the welfare evaluation is made using the egalitarian equivalent measures described in the second project, and explore the optimal treatment rules that arise.

Below, I offer an informal discussion of the key points covered in this project. For complete proofs and technical details, please refer to the paper.

Statistical Decision Theory

The optimal treatment choice apparatus described in Manski 2024 is based on statistical decision theory. Let's first describe what this theory aims to do and how it differs from the standard treatment evaluation methodology based on hypothesis testing.

When it comes to optimal treatment assignment, traditional methods based on hypothesis testing and statistical decision theory have distinct goals. The methods based on hypothesis testing typically focus on obtaining quality estimates of the treatment effects and then deciding whether the estimates are precise enough to justify a particular treatment choice, often emphasizing statistical significance and confidence intervals. In contrast, statistical decision theory shifts the focus entirely to the quality of the decision. It asks, “How good is this decision in terms of outcomes?” rather than, “How precisely have we estimated the treatment effect?” By prioritizing decisions over estimates, statistical decision theory ensures that the treatment assignment process is aligned as closely as possible with what evaluators truly wants more of (and what they might want to avoid), even when precise estimation is challenging, impossible, or of secondary importance.

There are several variants of statistical decision theory, and in this project we work with three of them: Bayesian, maximin, and minimax regret. Each of these three variants first begins by identifying a function that maps incomes to welfare (the evaluator's objective function), and then representing uncertainty about the effect of treatments on outcomes using a set of states of the world. What differs between the approaches is how this welfare is evaluated, compared and aggregated across states.

The Bayesian evaluator selects the treatment that leads to the highest expected welfare, where the expectation is taken with respect to a probability measure (called the prior) over the set of states.

The maximin evaluator avoids the specification of priors and defines the security welfare of a treatment rule to be given by the worst welfare across states that the rule could produce. The evaluator then selects the rule with the greatest security welfare.

The minimax regret evaluator also avoids the specification of priors and defines the regret of a treatment rule at a state to be the difference between the welfare achieved by the best treatment given knowledge of the state and the welfare achieved by the treatment rule at the state. The worst regret of a treatment rule is the largest regret the treatment rule achieves across states. The evaluator then selects the rule with the smallest worst regret.

Let's illustrate how these decision theories work with a variant on the main example in Social Preferences Under Uncertainty and Ambiguity.

Assume that the evaluator represents the uncertainty about what outcome arises with a given treatment through a set of two states of the word. Treatment \(a\) is associated with outcome \(y^{s}(a)\) in state \(s\) and a prospect, \(y(a)\), collects the possible outcomes induced by treatment \(a\) across the two states. Similarly for treatment \(b\) and associated prospect \(y(b)\).

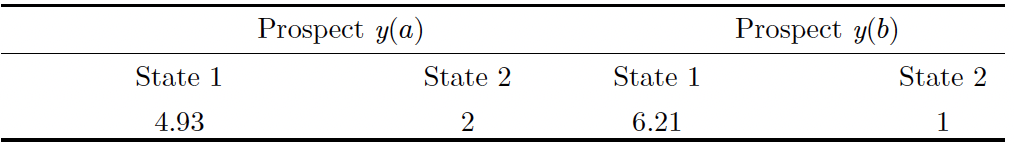

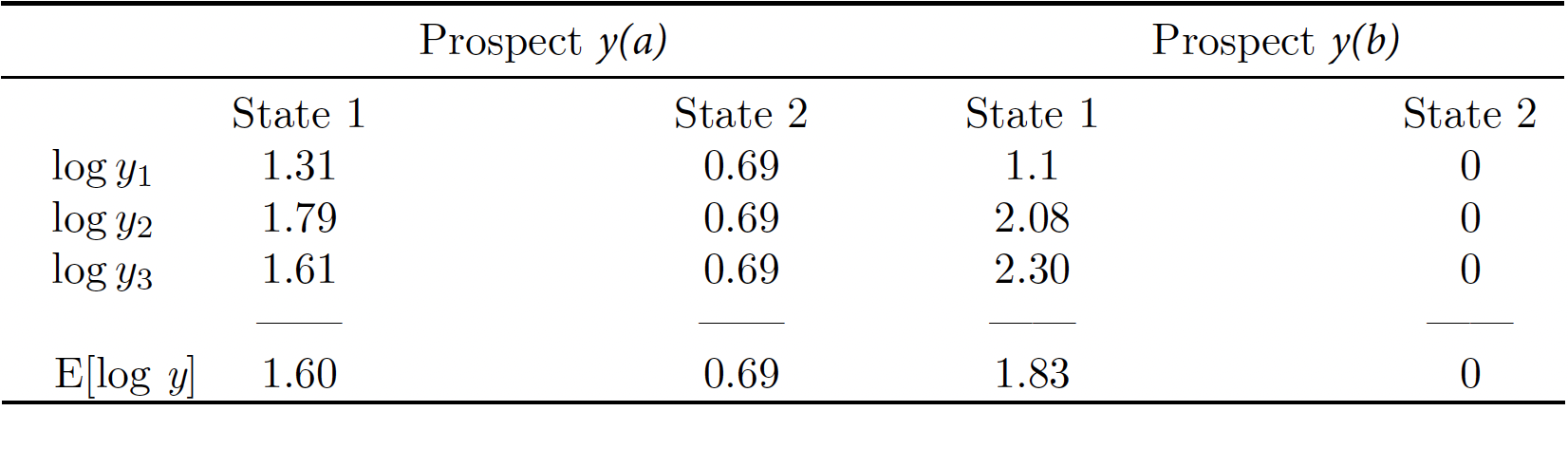

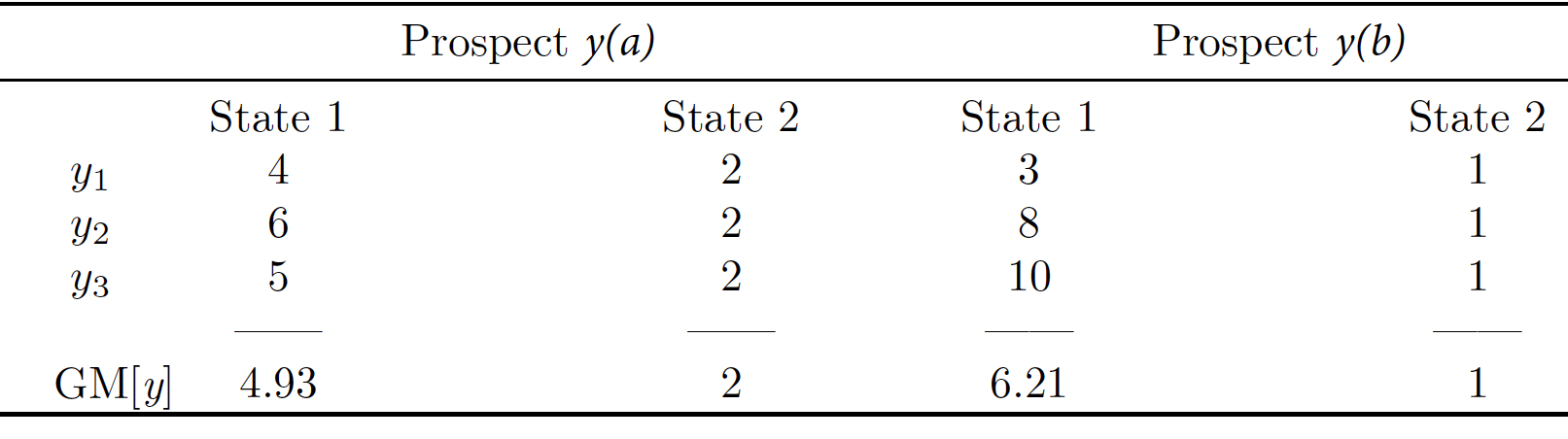

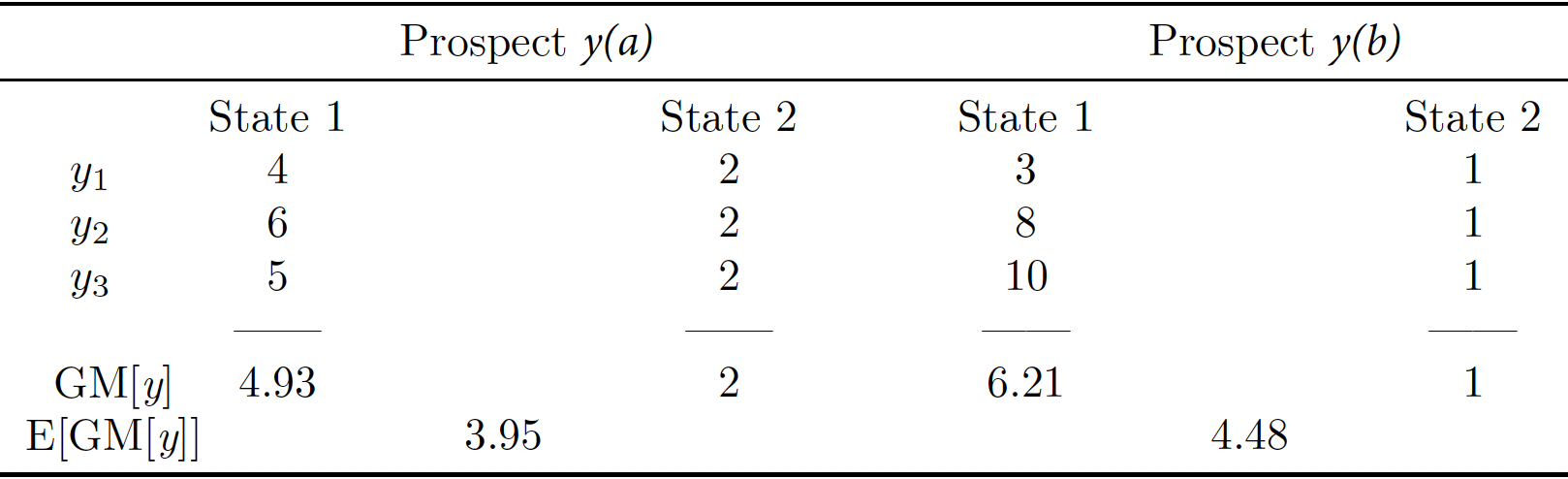

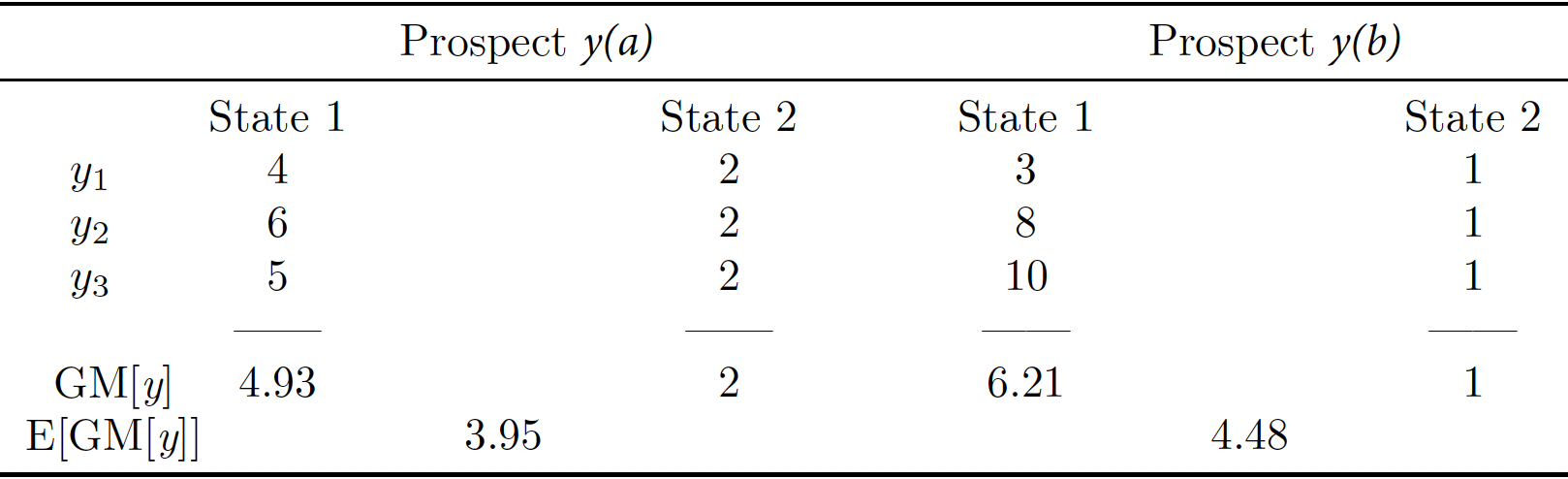

Our example is depicted in the table below:

The interpretation is as follows: treatment \(a\) yields outcome \(4.93\) in state 1 and \(2\) in state 2, whereas treatment \(b\) yields outcome \(6.21\) in state 1 and \(1\) in state 2. One can think about thhose numbers as providing a specific summary of how different individuals fare in each state, and where they come from need not concern us here, although I will have more to say about that question below. Let's for now take these numbers as given.

A treatment rule assigns individuals to treatments and in the example I focus on treatment rules that assign all individuals to the same treatment.

Let's first investigate how a Bayesian evaluator would choose among treatments. In addition to the state space described above, the Bayesian evaluator would assign probabilities to the states. Assume that our evaluator assigns probability \(\frac{2}{3}\) to state \(1\) and probability \(\frac{1}{3}\) to state \(2\). Then the expected outcome would be \(\frac{2}{3} 4.93 + \frac{1}{3} 2 = 3.95\) for treatment \(a\) and \(\frac{2}{3} 6.2 + \frac{1}{3} 1 = 4.48\) for treatment \(b\). On the basis of these expected outcomes, the Bayesian evaluator would use a treatment rule that assign everyone to treatment \(b\).

Now let's investigate how a maximin evaluator would choose among treatments. The security welfare of the treatment rule that assigns everyone to treatment \(a\) is \(2\), whereas the security welfare of the treatment rule that assigns everyone to treatment \(b\) is \(1\). Therefore, the maximin evaluator would use a treatment rule that assign everyone to treatment \(a\).

Finally, consider how a minimax regret evaluator would choose among treatments. The treatment rule that assigns everyone to treatment \(a\) exhibits a regret of \(6.21 - 4.93 = 1.28\) in state \(1\) and a regret of \(0\) in state \(2\). The worst regret of the treatment rule that assigns everyone to treatment \(a\) is then \(1.28\) (the maximum between \(1.28\) and \(0\)). On the other hand, the treatment rule that assigns everyone to treatment \(b\) exhibits a regret of \(0\) in state \(1\) and a regret of \(2 - 1 = 1 \) in state \(2\). The worst regret of the treatment rule that assigns everyone to treatment \(b\) is then \(1\) (the maximum between \(1\) and \(0\)). This means that the treatment rule with the smallest worst regret is the one that assigns everyone to treatment \(b\) (since \(1 < 1.28\)), and that is the rule that a minimax regret evaluator would choose.

Incorporating Inequality Aversion

In Social Preferences under Uncertainty and Ambiguity I used an example involving three individuals and two states of the world to make the case that, in a situation involving uncertainty, the decision of a Bayesian decision maker would vary depending on what representation of their social preferenes under certainty one brings into the decision analysis and and if you haven't read it yet I recommend that you do so at this point.

I will use the same example here to make the four main conceptual points of the present project, as shown below:

When the presence of sufficient data allows the evaluator to know the true state of the world (the so-called point identification case), the optimal treatment assignment problem:

Has the same answer for all the statistical decision theories we're considering (Bayesian, maximin, minimax regret).

Has the same answer regardless of what representation of the social preferences under certainty the evaluator is using.

When the presence of even very large amounts of data does not allows the evaluator to know the true state of the world (the so-called partial identification case), the optimal treatment assignment problem:

Generally varies depending on which statistical decision theory we will be considering.

Generally varies depending on which representation of the social preferences under certainty one brings into the analysis under uncertainty and ambiguity.

Points 1 and 3 above have been made by Manski 2024. Points 2 and 4 are novel.

Let's take a look at the example again and see how it can help us illustrate and make the points above.

The Illustration

Recall that prospect \(y(a)\) collects the possible outcome distributions induced by treatment \(a\) across all states of the world. Similarly for treatment \(b\) and associated prospect \(y(b)\).

In the example, prospect \(y(a)\) is given by \(\left[\begin{smallmatrix} 4 & 2\\ 6 & 2\\ 5 & 2 \end{smallmatrix}\right]\) whereas prospect \(y(b)\) is given by \(\left[\begin{smallmatrix} 3 & 1\\ 8 & 1\\ 10 & 1 \end{smallmatrix}\right]\), where rows correspond to individuals and columns corresponds to states.

Our evaluator is inequality averse and evaluates outcome distributions for each state \(s\) using the magnitude \({\frac{1}{3}}(f(y_1^s) + f(y_2^s) + f(y_3^s))\), where \(f\) is a strictly increasing and strictly concave function. In this example, we let \(f(y)=\ln y\).

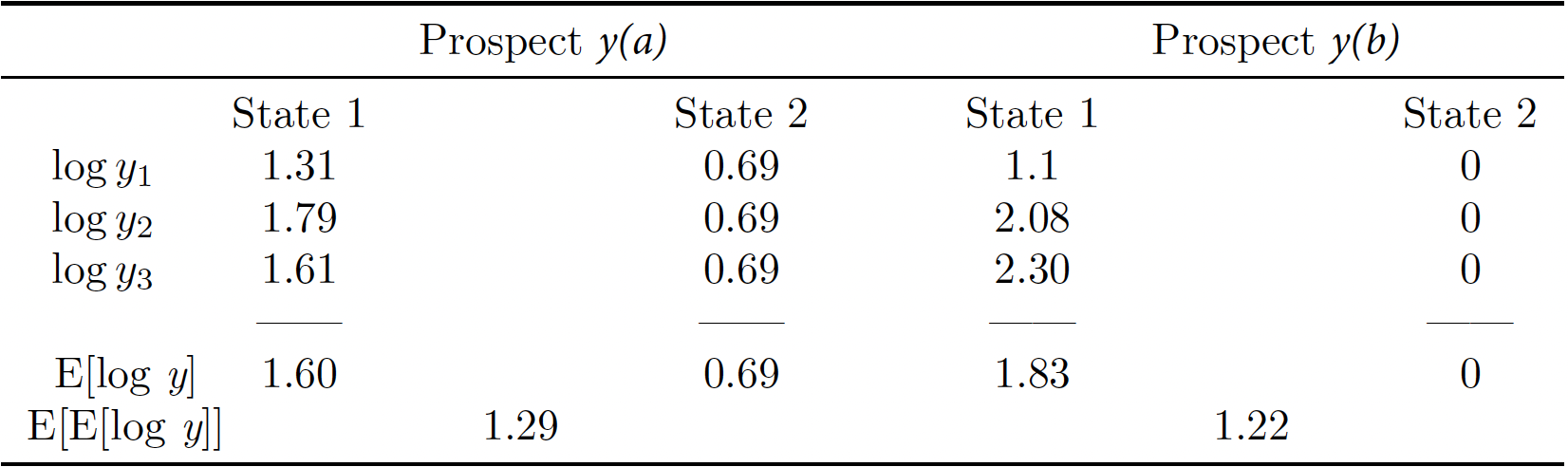

These computations are shown, for prospects \(y(a)\) and \(y(b)\), in the row labeled \(\mathrm{E}[\mathrm{log} \, y]\) in Table 1 below:

Table 1

Now let's consider in some detail how the illustration helps us make the main conceptual points of the paper.

A Bayesian evaluator would put probability 1 on the true state and select a treatment rule that assigns everyone to treatment \(b\) in state 1 (since \(1.83 > 1.60\)) and assigns everyone to treatment \(a\) in state 2 (since \(0.69 > 0\)).

When the known state is state 1, a maximin evaluator would trivially assing a security welfare of \(1.60\) and \(1.83\) to assigning everyone to treatments \(a\) and \(b\), respectively. In turn, when the known state is state 2, the maximin evaluator would trivially assing a security welfare of \(0.69\) and \(0\) to assigning everyone to treatments \(a\) and \(b\), respectively. Consequently, the maximin evaluator would select a treatment rule that assigns everyone to treatment \(b\) in state 1 (since \(1.83 > 1.60\)) and assigns everyone to treatment \(a\) in state 2 (since \(0.69 > 0\)).

A minimax regret evaluator would exhibit, in state 1, a regret of \(1.83 - 1.60 = 0.23\) to the treatment rule that assigns everyone to treatment \(a\), and that would trivially be the worst regret, since the only state considered possible at state 1 is precisely state 1. On the other hand, the treatment rule that assigns everyone to treatment \(b\) exhibits a regret of \(0\) in state \(1\), and that would trivially be the worst regret for the same reason given above. A minimax regret evaluator would exhibit, in state 2, a regret of \(0\) to the treatment rule that assigns everyone to treatment \(a\), and that would trivially be the worst regret, since the only state considered possible at state 2 is precisely state 2. On the other hand, the treatment rule that assigns everyone to treatment \(b\) exhibits a regret of \(0.69 - 0 = 0.69 \) in state \(2\), and that would trivially be the worst regret for the same reason given above. Therefore, if the state is known, and happens to be state 1, the treatment rule that minimizes worst regret is the treatment rule that assigns everybody to treatment \(b\). Similarly, if the state is known, and happens to be state 2, the treatment rule that minimizes worst regret is the treatment rule that assigns everybody to treatment \(a\).

In other words, when the state is known, all three decision theories execute the same comparison of known distributions of the outcome variable across treatment rules, and therefore arrive at the same optimal treatment rule.

Table 2

Now let's consider how the information in Tables 1 and 2 help us see how the choice of representation of the social preferences under certainty is irrelevant under point identification.

First, notice that the treatment rule that assigns everyone to treatment \(b\) is ranked above the treatment rule that assigns everyone to treatment \(a\) in state 1 according to both the \(\mathrm{E}[\mathrm{log} \, y]\) and the \(\mathrm{GM}[y]\) measures: looking at the corresponding rows from Tables 1 and 2 above, in the state 1 columns, we obtain that \(1.83 > 1.60\) and \(6.21 > 4.93\). Notice also that the treatment rule that assigns everyone to treatment \(a\) is ranked above the treatment rule that assigns everyone to treatment \(b\) in state 2 according to both the \(\mathrm{E}[\mathrm{log} \, y]\) and the \(\mathrm{GM}[y]\) measures: again, looking at the corresponding rows from Tables 1 and 2 above, in the state 2 columns, we obtain that \(0.69 > 0\) and \(2 > 1\). Therefore, both of these measures rank the prospects in the same way, on a state by state basis. This is simply due to the fact that these representations can be obtained from one another via a monotone transformation. In other words, when we have reached certainty or near certainty about the true state of the world, it does not matter which representation we use. They all give the same, correct answer.

Table 2 (Expanded)

Let's first investigate how a Bayesian evaluator would choose among treatments. If the evaluator assigns probability \(\frac{2}{3}\) to state \(1\) and probability \(\frac{1}{3}\) to state \(2\), the expected outcome would be \(3.95\) for treatment \(a\) and \(4.48\) for treatment \(b\). On the basis of these expected outcomes, the Bayesian evaluator would use a treatment rule that assign everyone to treatment \(b\).

Now let's investigate how a maximin evaluator would choose among treatments. The security welfare of the treatment rule that assigns everyone to treatment \(a\) is \(2\), whereas the security welfare of the treatment rule that assigns everyone to treatment \(b\) is \(1\). Therefore, the maximin evaluator would use a treatment rule that assign everyone to treatment \(a\).

Finally, consider how a minimax regret evaluator would choose among treatments. The treatment rule that assigns everyone to treatment \(a\) exhibits a regret of \(6.21 - 4.93 = 1.28\) in state \(1\) and a regret of \(0\) in state \(2\). The worst regret of the treatment rule that assigns everyone to treatment \(a\) is then \(1.28\). On the other hand, the treatment rule that assigns everyone to treatment \(b\) exhibits a regret of \(0\) in state \(1\) and a regret of \(2 - 1 = 1 \) in state \(2\). The worst regret of the treatment rule that assigns everyone to treatment \(b\) is then \(1\). This means that the treatment rule with the smallest worst regret is the one that assigns everyone to treatment \(b\), and that is the rule that a minimax regret evaluator would choose.

In this example, the Bayesian and the minimax regret evaluators both assign everyone to treatment \(b\), whereas the maximin evaluator would assign everyone to treatment \(a\).

To provide further clarity on extent of their agreement or disagreement of different kinds of evaluators among themselves, assume now that the Bayesian evaluator assigns probability \(\frac{1}{3}\) to state \(1\) and probability \(\frac{2}{3}\) to state \(2\), the expected outcome would be \(2.98\) for treatment \(a\) and \(2.74\) for treatment \(b\). Were this to be the case, the Bayesian and the maximin evaluators would both assign everyone to treatment \(a\), whereas the minimax regret evaluator would assign everyone to treatment \(b\).

The example therefore shows how all three of these decision theories arrive at potentially different optimal treatment rules under partial identification.

Let's review the example again by examining an expanded version of Table 1:

Table 1 (Expanded)

From the examination of the expanded Table 1 we learn that, if the evaluator computes, for each state \(s\), the magnitude \({\frac{1}{3}}(\ln y_1^s + \ln y_2^s + \ln y_3^s)\), the Bayesian evaluator would assign everyone to treatment \(a\), since the expected value of these (average) log measures across states is \(1.29\) for treatment \(a\) and \(1.22\) for treatment \(b\).

On the other hand, consider the expanded Table 2 again. This table summarizes the performance of the two treatments for each state using egalitarian equivalent measures.

Table 2 (Expanded)

From the examination of the expanded Table 2 we learn that, if the evaluator computes, for each state \(s\), the magnitude \((y_1^s y_2^s y_3^s)^{\frac{1}{3}}\), the Bayesian evaluator would assign everyone to treatment \(b\), since the expected value of these geometric mean measures across states is then \(3.95\) for treatment \(a\) and \(4.48\) for treatment \(b\).

This shows that the choice of representation of the social preferences under certainty matters under partial identification when solving a Bayesian optimal treatment assignment problem.

Let's now see whether the optimal treatment assignment for the maximin evaluator depends on the choice of representation of the evaluator's social preferences under certainty.

Table 1 reveals that the security welfare of the treatment rule that assigns everyone to treatment \(a\) is \(0.69\), whereas the security welfare of the treatment rule that assigns everyone to treatment \(b\) is \(0\). Therefore, the maximin evaluator would use a treatment rule that assign everyone to treatment \(a\).

Similarly, Table 2 reveals that the security welfare of the treatment rule that assigns everyone to treatment \(a\) is \(2\), whereas the security welfare of the treatment rule that assigns everyone to treatment \(b\) is \(1\). Therefore, the maximin evaluator would use a treatment rule that assign everyone to treatment \(a\).

We learn from this example that, under both representations of the social preferences of the evaluator under consideration (the \({\frac{1}{3}}(\ln y_1^s + \ln y_2^s + \ln y_3^s)\) representation and the \((y_1^s y_2^s y_3^s)^{\frac{1}{3}}\) representation), the maximin evaluator assigns everyone to treatment \(a\).

Last, let's consider the minimax regret evaluator. Using the information in Table 1, we see that the treatment rule that assigns everyone to treatment \(a\) exhibits a regret of \(1.83 - 1.60 = 0.23\) in state \(1\) and a regret of \(0\) in state \(2\). The worst regret of the treatment rule that assigns everyone to treatment \(a\) is then \(0.23\). On the other hand, the treatment rule that assigns everyone to treatment \(b\) exhibits a regret of \(0\) in state \(1\) and a regret of \(0.69 - 0 = 0.69 \) in state \(2\). The worst regret of the treatment rule that assigns everyone to treatment \(b\) is then \(0.69\). This means that the treatment rule with the smallest worst regret is the one that assigns everyone to treatment \(a\), and that is the rule that a minimax regret evaluator would choose under the \({\frac{1}{3}}(\ln y_1^s + \ln y_2^s + \ln y_3^s)\) representation.

We also saw earlier, using the information in Table 2, that the treatment rule that assigns everyone to treatment \(a\) exhibits a regret of \(6.21 - 4.93 = 1.28\) in state \(1\) and a regret of \(0\) in state \(2\). The worst regret of the treatment rule that assigns everyone to treatment \(a\) is then \(1.28\). On the other hand, the treatment rule that assigns everyone to treatment \(b\) exhibits a regret of \(0\) in state \(1\) and a regret of \(2 - 1 = 1 \) in state \(2\). The worst regret of the treatment rule that assigns everyone to treatment \(b\) is then \(1\). This means that the treatment rule with the smallest worst regret is the one that assigns everyone to treatment \(b\), and that is the rule that a minimax regret evaluator would choose under the \((y_1^s y_2^s y_3^s)^{\frac{1}{3}}\) representation.

This shows that the choice of representation of the social preferences under certainty matters under partial identification when solving a minimax regret optimal treatment assignment problem.

To conclude, the choice of representation of the social preferences under certainty matters under partial identification in this example for the Bayesian and the minimax regret evaluator. It has no effect on the choice of the maximin evaluator.

The Rest of The Paper

In the preceding paragraphs, I introduced the key ideas of this research project through simple examples. The paper develops these points in full generality while also making several additional contributions:

In the context of a binary choice between a known status quo treatment and an innovation, I demonstrate that inequality aversion increases the likelihood that both Bayesian and minimax regret evaluators will adopt the innovation.

Using the limit of experiments framework, I derive inequality-sensitive, asymptotically Bayes-optimal and minimax regret-optimal statistical treatment rules.

I illustrate the proposed methodology through two applications: the Job Corps education and training program for disadvantaged youth and Rachael Meager’s Bayesian meta-analysis of the microcredit literature.

For a full exposition, see the paper.